Seth Godin Will No Longer Publish Books Traditionally

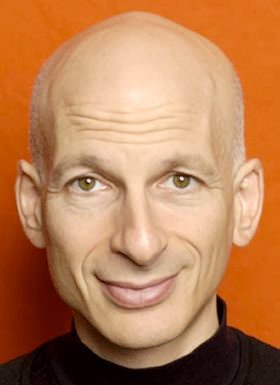

New York Times bestselling author and marketing guru, Seth Godin vows to never publish traditionally again. After over 12 books with a legacy publisher, Godin says he’s had enough.

In my interview with him today for an upcoming Mediabistro feature, Godin says, “I’ve decided not to publish any more books in the traditional way. 12 for 12 and I’m done. I like the people, but I can’t abide the long wait, the filters, the big push at launch, the nudging to get people to go to a store they don’t usually visit to buy something they don’t usually buy, to get them to pay for an idea in a form that’s hard to spread … I really don’t think the process is worth the effort that it now takes to make it work. I can reach 10 or 50 times as many people electronically. No, it’s not ‘better’, but it’s different. So while I’m not sure what format my writing will take, I’m not planning on it being the 1907 version of hardcover publishing any longer.” (via Mediabistro)

I’ve been anticipating this announcement, but I’m no less impressed, intrigued and thrilled to see Seth Godin stepping up the the plate. The landscape is going fluid, folks! Exciting times. Goodbye Gutenberg Paradigm, hello Socratic paradigm. It’s time for storytelling 2.0!

Godin announced this morning that “Linchpin will be the last book I publish in a traditional way.” He goes on to describe the recalcitrance and fear so pervasive in the traditional publishing world today. And he unabashedly steps away from it!

As the medium changes, publishers are on the defensive…. I honestly can’t think of a single traditional book publisher who has led the development of a successful marketplace/marketing innovation in the last decade…

My audience does things like buy five or ten copies at a time and distribute them to friends and co-workers. They (you) forward blog posts and PDFs. They join online discussion forums. None of these things are supported by the core of the current corporate publishing model.

Since February, I’ve shared my thoughts about the future of publishing in both public forums and in private brainstorming sessions with various friends in top jobs in the publishing industry. Other than one or two insightful mavericks, most of them looked at me like I was nuts for being an optimist. One CEO worked as hard as she could to restrain herself, but failed and almost threw me out of her office by the end. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t heartbroken at the fear I saw. (via Moving On)

I look forward to supporting and encouraging Seth Godin as he wades into these exciting new waters. Fear be damned, Seth Godin is moving on…What about you?